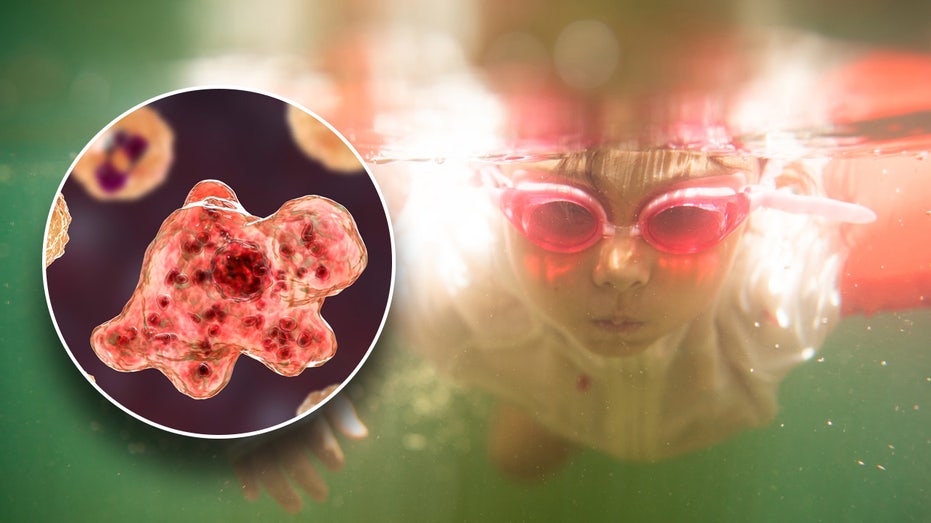

Cooling off in lakes, rivers and streams is a hallmark of the summer — but for an unlucky few, it can lead to an infection caused by Nagleria fowleri, a bacteria more commonly known as the brain-eating amoeba.

In the U.S., there have been at least three reported deaths this year from the infection, which occurs when the bacteria enter the nose during submersion in fresh water, usually while swimming.

Nagleria fowleri can cause the deadly primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), which destroys brain tissue, according to the CDC.

GEORGIA TEEN GIRL IDENTIFIED AS RESIDENT WHO DIED OF BRAIN-EATING AMOEBA AFTER SWIMMING IN LAKE

Of the 157 people known to be infected in the U.S. between 1962 and 2022, only four individuals survived — meaning the death rate is more than 97%.

In late July, a 17-year-old Georgia girl, Morgan Ebenroth, died after becoming infected with the bacteria while swimming in a lake with friends.

Also in July, the Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health (DPBH) reported that a 2-year-old boy died after contracting a brain-eating amoeba infection from a natural hot spring.

And in February, a Florida man died after he was infected when washing his face and rinsing his sinuses with tap water containing Nagleria fowleri.

Fox News Digital spoke with Tammy Lundstrom, chief medical officer and infectious disease specialist for Trinity Health in Michigan, about the risks and the prevention of infection.

“The risk of brain-eating amoeba is very low,” she said. “Fewer than 10 people in the U.S. every year get infected — but unfortunately most cases are fatal. There are only a handful of survivors of known cases.”

The Southern U.S., with its warmer temperatures, has reported the most cases — 157 in total between 1962 and 2022, Lundstrom said.

Almost half of these occurred in Texas and Florida.

“However, there are a few even rarer cases reported from the northern states,” she said.

FLORIDA RESIDENTS WARNED ABOUT TAP WATER AFTER MAN DIES FROM BRAIN-EATING AMOEBA

The amoeba only lives in freshwater, so swimming in the ocean is not a risk, Lundstrom added.

Naegleria fowleri thrives in warm water, growing best at temperatures up to 115°F. This means that July, August and September are the highest-risk months, according to the CDC’s website.

Some experts believe that climate change could make Naegleria fowleri infections more common.

“As air temperatures rise, water temperatures in lakes and ponds also rise and water levels may be lower,” the CDC’s website states.

“These conditions provide a more favorable environment for the amoeba to grow.”

It also says, “Heat waves, when air and water temperatures may be higher than usual, may also allow the amebae to thrive.”

The initial symptoms of PAM usually begin about five days after exposure to the bacteria — but they can be noticed sooner.

Early signs usually include headache, nausea, fever and/or vomiting, per the CDC.

As the infection progresses, people may experience confusion, stiff neck, disorientation, hallucinations, seizures and coma.

COVID HOSPITALIZATIONS ARE ON THE RISE, COULD SIGNAL ‘LATE SUMMER WAVE,’ SAYS CDC

“People usually start to feel ill one to 12 days after the water exposure,” Lundstrom said. “Early symptoms should prompt a medical evaluation, as they are also signs of bacterial meningitis.”

Death can occur anywhere between one and 18 days of infection, with an average of five days.

The best way to prevent infection is to avoid putting your head in the water when swimming, Lundstrom told Fox News Digital.

“Infection occurs when water harboring the amoeba goes up a person’s nose, usually during swimming,” she said.

“It is not known why some people get infected and others, even swimming companions, do not.”

Drinking contaminated water does not cause infection, and it does not spread from one person to another, Lundstrom added.

Although a death was reported this year after a man was exposed to the bacteria while washing his face and clearing his sinuses with tap water, Lundstrom said this is a remote risk.

People can also use nose clips or hold the nose shut to prevent infection.

Because the bacteria is found in soil, the CDC also recommends avoiding stirring up the sediment at the bottom of lakes, ponds and rivers.

When a patient has been diagnosed with a brain-eating amoeba, treatment usually includes a variety of anti-fungal medications, including rifampin and azithromycin, Lundstrom said.

Miltefosine, a newer anti-fungal drug, has been shown to kill the bacteria in laboratory tests and was used to treat three of the surviving patients, the CDC states on its website.

“However, the effect of all of these drugs on actual infected people is unknown due to the high fatality rate,” Lundstrom noted.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

Those who experience sudden headache, fever, stiff neck or vomiting — especially if they have recently been swimming in warm freshwater — should seek immediate medical attention, the CDC recommends.

Despite the infection’s high fatality rate, Lundstrom emphasized the rarity of cases.

“Millions of people enjoy swimming every summer, but only a few become infected,” she said.

“The best protection would be to avoid immersing your head when swimming in the summer.”