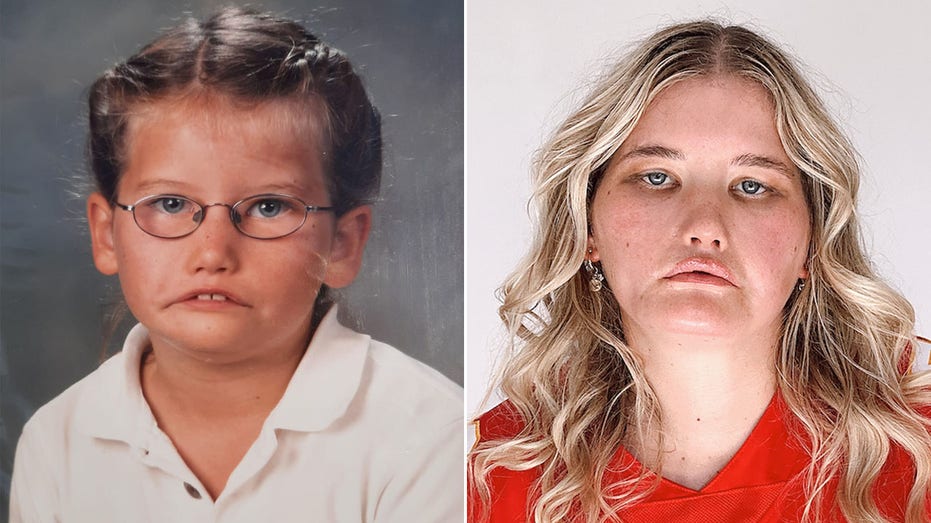

Tayla Clement, 26, was born with a rare disorder that has made it impossible for her to smile — but she says she is grateful for it.

Born and raised in New Zealand, Clement has Moebius syndrome, a neurological disease that affects one child out of every 50,000 to 500,000 born, research shows.

Moebius occurs when a baby’s facial nerves are underdeveloped. The primary effects are facial paralysis and inhibited eye movement, but the condition can also cause difficulty with speech, swallowing and chewing, according to Johns Hopkins.

RARE CONDITION CAUSED PATIENT TO SEE ‘DEMONIC’ FACES, SAYS STUDY ON ‘VISUAL DISORDER’

“The syndrome affects my sixth and seventh cranial nerve, so it’s essentially like facial paralysis,” Clement told Fox News Digital in an interview.

It also means Clement can’t move her eyebrows or upper lip — and can’t shift her eyes from side to side.

Dr. Juliann Paolicchi, a pediatric neurologist and the director of pediatric epilepsy at Staten Island University Hospital in New York, has treated several babies with Moebius syndrome. (He was not involved in Clement’s care.)

“Infants born with the syndrome may have a lopsided face, may not be able to form a smile, and may have feeding problems early in life,” he told Fox News Digital.

NEW JERSEY TWINS RECEIVE MATCHING HEART SURGERIES AFTER MARFAN SYNDROME DIAGNOSIS: ‘A BETTER LIFE’

They can also experience orthopedic anomalies, such as abnormal development of the fingers and feet.

“Other parts of the face and eyes may be affected, such as a small jaw, cleft palate and smaller-sized eyes,” Paolicchi added.

While children with Moebius syndrome do not have problems with intellectual development, social situations can be a challenge due to a decreased ability to demonstrate emotions with the face, Paolicchi said.

“They are often mistaken as being sad or overly serious, when they are simply just not able to smile,” he said.

Growing up without the ability to smile brought plenty of challenges for Clement, she said.

She was born in 1997, before the advent of social media, so she wasn’t able to connect with others facing the same challenge.

“With the syndrome being super rare and also coming from a small country, it was quite isolating,” she said.

Clement said she was bullied for years, “for as long as I can remember.”

“It started off as verbal bullying — being told that I was ugly or worthless, or being isolated and not having any friends.”

Things got worse when Clement was 11, after she had a major operation in an attempt to correct her inability to smile.

During the “invasive” nine-hour surgery, doctors took tissue from her right thigh and inserted it internally into the corners of her mouth and into her temples.

“The idea was that when I would clench down on my jaw, the tissue that was planted would pull the corners of my mouth up to mimic a normal smile,” she recalled to Fox News Digital.

OHIO BOY, 8, PREPARES FOR BLINDNESS: ‘IT’S HEARTBREAKING,’ HIS MOM SAYS

Paolicchi confirmed that corrective surgery is sometimes performed on babies and children with Moebius syndrome.

“The procedure, called the ‘smile’ surgery, helps not only appearance, but the ability to smile and to be able to pronounce words more clearly,” he said.

“This procedure does involve transferring portions of the person’s own muscle to the face and connecting it to the working nerves of the face. This is a complicated and specialized procedure and should only be performed by surgeons skilled in the procedure.”

The surgery does come with risks. Clement noted that there was a “very fine line” between tightening the area too much — which would leave her with a permanent smile — and leaving it too loose and not seeing any results at all.

“As an 11-year-old girl, I thought, if I could just smile, I would have friends and wouldn’t get bullied anymore. So I jumped at the opportunity,” she said.

The surgery was unsuccessful — leaving Clement scarred and “completely broken,” she said.

“It was such a horrible time for me,” she said. “But looking back on it now, I couldn’t be more grateful for the surgery being unsuccessful. I think it was all supposed to happen that way.”

After the operation, the bullying got worse. In addition to calling Clement names, students pushed her into lockers, ripped off her backpack and threw her items on the floor, she said.

“That came with a lot of mental health challenges,” she said. “For much of my childhood, I was quite depressed and anxious.”

While Clement’s family provided her with plenty of love and support — “they’re the reason why I’m still here,” she said — they didn’t know how bad things really were.

“When I was younger, I never told my parents about what I was going through with the bullying,” Clement said.

“There are still some things that I probably won’t ever tell them about, because I don’t want them to feel sad or upset,” she went on. “I know they would feel like they could have done something, but there’s nothing they could have done.”

In 2015, during her senior year of high school, Clement began collapsing and experiencing seizures.

The next year, at 18, she was diagnosed with extreme clinical depression and anxiety, along with post-traumatic stress disorder, she said.

“Because I had been through so much stress and trauma, my brain was kind of shutting down,” she said. “The seizures were like a physical form of how much I was struggling internally.”

OHIO MOTHER HOPES FOR A CURE TO SAVE HER SON, 8, FROM RARE, FATAL DISEASE: ‘GUT-WRENCHING’

At the time, doctors and specialists told Clement that she would have seizures for the rest of her life, and that she’d always be dependent on other people.

But she was determined to prove them wrong.

After her diagnosis, Clement underwent intensive therapy, which she said played a big part in her recovery.

She found herself at a “crossroads,” she said, where she had to choose between working on her mental and physical health and putting herself into a better space, or continuing to feel “unhappy and miserable.”

Clement chose the first path — although it wasn’t easy.

“There were days when I just wanted to give up. I didn’t want to do life anymore because it was so hard,” she said.

“I learned quite quickly that the only person who can truly help you is yourself.”

Clement “worked tirelessly,” continuing with therapy, reading many self-help books and adopting healthy daily routines.

“I just chose to believe in myself — and that I was destined for something bigger,” she said.

As it turned out, the “something bigger” was a new career in sports.

Clement had always been a big sports fan — with a particular love of rugby, which is very popular in New Zealand.

In March 2023, she started creating social media content around rugby and motorsports. The Chiefs, a professional rugby union team in New Zealand, gave Clement her first opportunity.

This year, Clement interviewed players from four of the Super Rugby Pacific teams, including some of the best players in the world, such as two-time World Rugby Player of the Year Beauden Barrett.

In her role as a sports content creator and host, Clement said she’s leveraged her love of rugby into a “new lease on life — a real purpose.”

Since entering the rugby scene, she has worked to “bring inclusion” into the sport, with a goal of “inspiring, empowering and advocating for positive change.”

Clement is also aiming, she said, to help other sports organizations incorporate more inclusion into their teams.

“I’ve known from a young age that I’m meant to help people,” Clement told Fox News Digital. “Using my story and my voice to advocate for others and make the sports arena more inclusive makes me so happy. And I’m just getting started.”

It has been three years since Clement experienced a collapse or seizure, she told Fox News Digital.

“I’m living a life I truly never could have dreamed of,” she said. “I’m doing a job that I absolutely love, and I just did not think this level of happiness and contentment was accessible or attainable for me … It’s been a long journey, and I’m very grateful for all of it.”

Clement has also used her platform to connect with other people who have syndromes or disabilities. Her mission is to educate others about how to treat younger people who feel like they are “not seen or heard” — whether that’s in the sports arena or everyday life.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

“I really needed someone like my present self when I was younger,” she said. “It’s a full-circle moment to be there for other people now.”

Despite the “dark times” she’s experienced, Clement said that being born with Moebius syndrome and not being able to smile has turned out to be “the greatest gift.”

“We’re all born different and unique,” she said. “It has given me the opportunity to use my voice and to be proud of my differences.”

“Being alive is such a gift, and it’s a special thing to be born with Moebius syndrome. It doesn’t make us any less worthy, beautiful or amazing.”

Even though she can’t smile in the traditional sense, Clement says she has her own version.

“I think everyone’s smile is different, just like everyone else is different,” she said.

“I just smile in my own way.”